Populist calls from left, right, centrist, and also green movements in Europe have been getting louder throughout the past few years. The label ‘populist’ is thrown around in discussions, the media, and parliamentary debates. But what is populism, and what dangers does it hold to the European Union? Politikorange editors Lukas Hinz and Leander Löwe tried to find out more about the occurrence of Populism.

Populism – The ‘Thin Ideology’

Populism appears in three different shapes. According to Hanspeter Kriesi, a well-respected political scientist from the European University Institute in Florence, it should be categorized as a discourse and communication style, as a political strategy and as an ideology. He is referring to one of the first definitions of populism developed by the Dutch political scientist and expert in populism and extremism Cas Mudde. According to him, the thought of dividing society is essential to populist ideology.

In his paper “The Populist Zeitgeist” from 2004, he describes how this thin ideology of populism

considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.”

Populists try to present the people as the sovereign in the state, and claim that “the elite has betrayed the sovereign”, Kriesi explains. He adds that populism can only exist in combination with ‘thicker,’ fake-ideologies that have strong content. This is why populism often appears (depending on the national context) in extreme right, centrist, and left parties and supports various ideas, which could not be more diverse.

Spoiler alert: Crises support Populism!

Populism is often successful during times of crisis. In his paper from 2013 Kriesi adds that this is most evident during political crises, which “[enhance] anti-elitism in the country in question” and economic ones, because they serve as a catalyst for political crises.

According to his research, Kriesi cites that “the combination of two types of crisis is the most favorable condition for populist mobilization”, and that populists are especially encouraged by the ‘losers’ of globalization.

Francis Fukuyama, Professor for History and Political Science at Stanford University, delivered a different explanation for the rise of populism in 2019. In an interview with Deutsche Welle, he says that people’s need for a common identity is greater than could be ever fulfilled by an open-minded and liberal society with “massive immigration and outsourcing measures”. In his book called “Identity”, he analyses one of the biggest consequences of this need: Identity politics.

According to Fukuyama’s book, identity politics means the conscious representation of one’s own interests and the associated delimitation and exclusion of other ideas and of dissenters. In combination with populism, these can become very dangerous for both democracy and global politics. The main reason is that identity politics places the identity of groups above that of others, thus making compromises more difficult, which are essential for a basic democratic and multilateral order.

For Fukuyama, a growing need for identity could also be a main driver of the European Union’s struggle with populism. Because the European Union never created an extended European identity, citizens have a more intense connection to their national states. That strengthens euro-skepticism in the member states.

The trend has been confirmed by numerous studies: for example, “National and/or European identity?: Issues of self-definition and their effect on the future of integration“ conducted by the Hungarian Political Capital Policy Research and Consulting Institute and the German Friedrich-Ebert Foundation „.The study from 2013 states that “according to surveys, the primacy of national identity is unchallenged in all cases.” This could be one of the reasons why, according to SPIEGEL, left and right populism almost always go hand in hand with skepticism towards the European Union. But what do the actual programs of populists look like?

The Different Faces of Populism

Today, populist parties are attracting voters in almost all EU-member states. The political directions of these parties vary vastly. The different ways a populist party can go are illustrated by the Manifesto-Project initiated by the WZB Social Science Research Center Berlin.

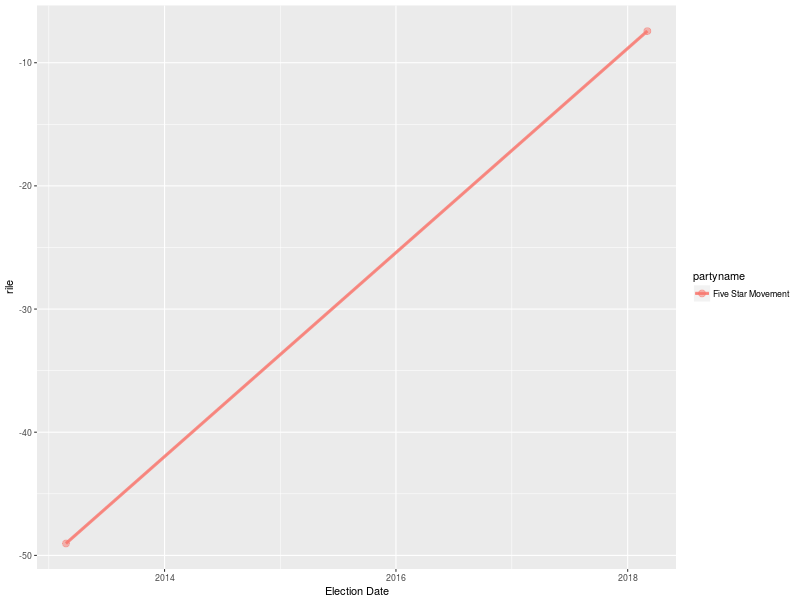

A prominent example for a populist party which shifted its direction entirely is the Movimento Cinque Stelle in Italy (short: M5S, Engl. the Five Stars Party). Originally founded by the Italian comedian Beppe Grillo with a green-left agenda, it further and further moved to the right with increasing migration and the upcoming need for identity. The right-left-index of the Manifesto-Project is a piece of evidence for this.

Source: Volkens, Andrea / Burst, Tobias / Krause, Werner / Lehmann, Pola / Matthieß Theres / Merz, Nicolas / Regel, Sven / Weßels, Bernhard / Zehnter, Lisa (2020): The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2020a. Berlin: Wis-senschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2020a

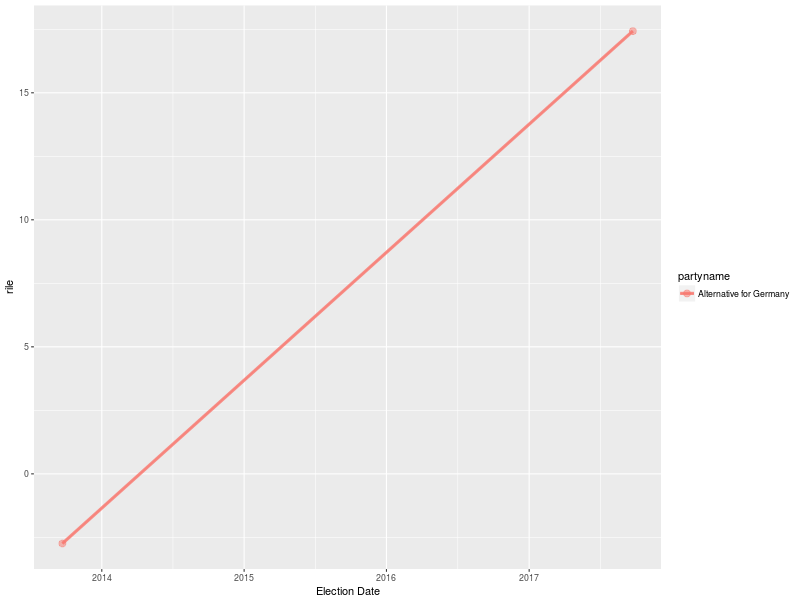

Similarly, the German AfD started out with the euro-skeptic liberal program and moved to the extreme right between its foundation in 2013 and 2020.

Source: Volkens, Andrea / Burst, Tobias / Krause, Werner / Lehmann, Pola / Matthieß Theres / Merz, Nicolas / Regel, Sven / Weßels, Bernhard / Zehnter, Lisa (2020): The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2020a. Berlin: Wis-senschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2020a

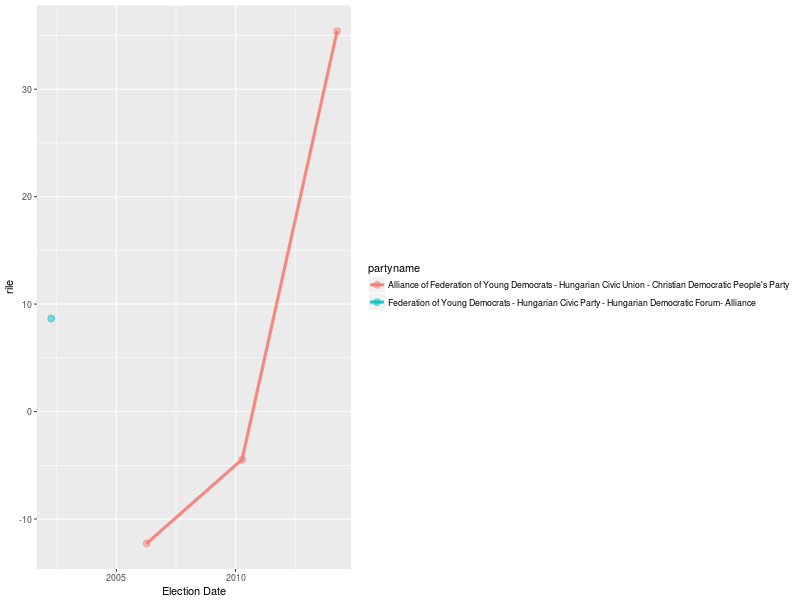

Another prominent example of how ‘thin’ the ideology of populism itself is – and of how much the agenda of a party can shift – can be seen in Hungary. The Fidesz Party was initially founded as a liberal protest movement. Nowadays, party-leader and prime minister Victor Orbán is setting the stage to turn Hungary into a right-extremist autocracy. Even in Portugal, which had no populist party for years, the right-extreme populist party “Basta!” (“Enough!”) is on the rise, as POLITICO showed in 2019. Its motto: Being “Anti-party, anti-immigrant, Eurosceptic”.

Source: Volkens, Andrea / Burst, Tobias / Krause, Werner / Lehmann, Pola / Matthieß Theres / Merz, Nicolas / Regel, Sven / Weßels, Bernhard / Zehnter, Lisa (2020): The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2020a. Berlin: Wis-senschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2020a

EU-Presidency 2020: Example of how to Deal with Populists

The European Union developed its own strategy to handle populist ideologies in its middle over the years. This is especially evident in 2020: As observed by the Associated Press, populists in Europe were weakened during the corona crisis. Angela Merkel’s speech in the European Parliament, where she took a stand against the division of the European society by the populists, underlines this. In her speech, she highlighted that “Germany is prepared to show extraordinary solidarity”, and that the pandemic is revealing the limits of populism in Europe.

In her speech to mark the start of the EU Presidency on July 1, she urged the member states of the EU to confirm the recovery package for the European economy, amounting to more than 750 billion Euros. Therefore populists would be deprived of any benefits from the corona crisis: “We are seeing at the moment that the pandemic can’t be fought with lies and disinformation, and neither can it be with hatred and agitation. Fact-denying populism is being shown its limits.” While Hanspeter Kriesi says that especially crises help populist parties to rise, the corona crisis seems to have had the contrary effect. According to Merkel, solidarity among member states is the most effective way to take a stand against the voice of populist parties in the European countries.